The American public’s intrigue over zombies and the living dead have led to the creation of a multibillion-dollar market through video games, television shows, movie franchises, and novels since “zombies” first entered our collective conscience in the 1930’s, following the U.S. occupation of Haiti from 1915-135, and the 1929 publication of William Seabrook’s title, The Magic Island.

With Halloween this coming Saturday, you’re sure to see a number of zombie children hobbling around the neighborhood, collecting sweet treats from neighbors and friends, recreating personages seen in shows like The Walking Dead, or incarnated in any number of popular video games.

But where does our idea of a zombie come from? And aren’t you just a little bit surprised that “zombies” have existed in our American narrative for fewer than 100 years?

Our word “zombie” comes from Haiti’s, “zonbi”, which can be traced even further back to the Fon language in Western Africa. Maybe that’s not surprising; after all, the idea of the “living dead” fits perfectly into Americans’ misconception of voodoo (voudou) as an exclusively dark-magic cult.

But we’ve taken the notion of a zombie so far out of its original context, that the American zombie is diluted to little more than an animated corpse wandering aimlessly across the Earth. While zombies might give us a thrilling fright, for Haitians, the zonbi embodies a much more profound and historically based fear.

So here’s a real zonbi story for you:

From the time West African slaves arrived on the French Colony of Saint-Domingue they faced abhorrent conditions and abominable cruelty at the hands of their masters and overseers. Life for a slave in Saint-Domingue was so bad that death was regarded as a moment of liberation from the cruelty of this world, a chance for a slave’s soul to return to their homeland, Ginen.

Death was something that many longed for, and although many slaves committed suicide rather than face the daily horrors of slavery, suicide didn’t offer freedom; instead, the deceased would be forced to remain on Saint-Domingue, forever wandering, enslaved to their own flesh, without the hope of ever returning to their homeland in Guinea, a zonbi.

When slavery ended with Haitian Independence in 1804, the anxiety of bondage persisted in the Haitian psyche and the notion of the zonbi continued to evolve.

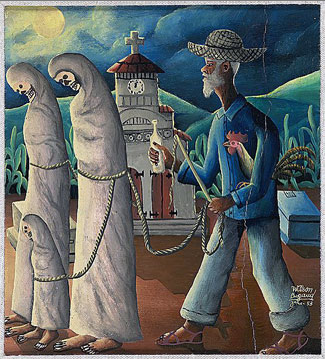

Bokors (voudou priests who are said to “serve-with-both-hands” – practicing both good and dark-magic to serve their own selfish interests) used their knowledge to enslave the deceased, creating zonbis who mindlessly carry out their tasks and purposes.

Stories continue to perpetuate in Haiti of loved ones, long since deceased, who are seen in the service of a bokor – where they are subject to all of the cruelties of slavery lived over again in the next life.

“Zonbi” (1939) by Haitian Artist Wilson Bigaud Image provided courtesy of University of Michigan

It’s important to understand that for Haitians, the zonbi exists outside of the realm of regular voudou practice. It is always the work of a wicked bokor and never the creation of a hougan or mambo, who would never use their knowledge to impose such a cruel fate.

Loved ones hoping to protect the deceased undertake measures to make sure that their loved one is not forced into servitude. By burying them alongside daggers they hope the deceased will be able to protect themselves should a bokor try to lure them from their rest.

Part of the folklore goes that a person must respond to their name before a bokor can turn them into a zonbi, so some might scatter mustard seeds throughout the coffin, or place an eyeless needle and piece of thread next to the deceased. In this way, they hope that the impossible task of threading an eyeless needle, or counting an innumerable quantity of mustards seeds might occupy the deceased long enough to keep them from responding to their name.

In Haiti, the zonbi is not a sensationalized fantasy created by storytellers to thrill avid listeners; it is a pernicious fear materialized after centuries of oppression and slavery that have deeply impacted Haiti’s spirit. For Haitians, the notion of the zonbi serves as a constant reminder of how precious and fragile a thing freedom continues to be – now there’s a scary thought for you this Halloween.

Written by Erin Nguyen on October 29, 2015

Want to read more? We are hardly the experts on zonbi, or the surrounding socio-religious practices associated with voudou in Haiti, but here are some of the sources we visited to create this article:

Voodoo in Haiti, by Alfred Métraux

The Tragic, Forgotten History of Zombies, article by Mike Mariani, The Atlantic

Zombies worth over $5 billion to economy, article by John Ogg, NBC News

Zoinks! Tracing the History of “Zombie” from Haiti to the CDC, article by Lakshmi Ghandi, NPR